This essay was first published on niume.com

In 2008, Mandy Chang directed the television documentary The Mona Lisa Curse, written and presented by renowned art critic/historian/observer New York resident, all-round Aussie larrikin, the late Robert Hughes.

It’s available to view on the internet. Last time I saw it on Vimeo.

By and large, Hughes’ scathingly incisive polemic was a breath of fresh air, exposing the carefully constructed and cultivated culture of the industrialisation of art exploitation, the audacious overvaluing of contrivances that amounted to little more than custom-generated token baubles. It threw a spotlight on the 20th/21st century’s Emperor’s New Clothes syndrome, rampant in what has been repeatedly described as one of the largest unregulated industries in the world.

Boldly illustrated in the documentary was the intensely uncomfortable Robert Scull art sale at Sotheby’s New York in 1973, a hustler cashing in on an American society impatient to establish for itself its own deeper heritage, desperate to validate empire built on foundations aspiring to greater substance than European-reject religious fundamentalist colonies. That bid to evoke icons of permanence was looking for newer ways than its public buildings mimicking icons of ancient European empire, complete with Greco-Roman pediments, fluted columns and allegorical statuary. Now all of that would find itself culturally eclipsed by paintings of comic-strip fighter jets and icons of mass production, entertainment and consumption.

The artists themselves – those original architects of that new-found cultural expression – ended up left comparatively destitute, tossed crumbs permitting basic sustenance and maybe a new tube of paint or two, promised recognition ultimately proving hollow, given how subsequent galleries and other middle men would glean their own major share of the takings. These middle men and their eager assurances to both patrons and the artists themselves that artists were in it for the art, not the money, pocketed the majority of loot for themselves. Only in more recent times when art-world superstars such as Koons and Hirst were able to sell directly did any creative see an appropriate benefit for themselves, but as Hughes so wryly observed, what these self-branded art world icons were producing was not really about art, more cultivating an image that would guarantee their business of dominating the money-making aspect of what is currently marketed as “art”, something that built a bubble which not only burst, but has re-formed, larger, glitzier and more ponderous than before.

The business of art now more than ever has taken precedent, sending any artist incapable of hustling to the wall, where any work is valued not by its aesthetic, cultural or compositional merit, nor by its craftsmanship or storytelling capability, but almost purely by an arbitrarily contrived price tag, determined by where and by whom it is sold. Staggering sums paid for some works bare little to no relation to the actual value of the works themselves, more a reflection of market context, manipulation and control. Some contemporary works have extremely high merit, yet languish in obscure galleries for far too long, their price tags a mere fraction of other works that are little more than well presented rubbish. Much of that art is bought and then stored, a commodity to be traded rather than beauty to be enjoyed or culture to be celebrated.

That this phenomenon sprang out of the United States, and in particular New York, rather than – say – London, Berlin, Tokyo, Shanghai or Paris, comes as little surprise. A long-established aspect of American culture is the exaltation of money and the monied (a vestige of British aristocratic attitudes of caste), a curious philosophy that is prevalent in the United States far and beyond anywhere else in the world (with oligarchic Russia and upcoming China in close pursuit). If you have enough money – the idea goes – you must be a wonderful person, and the more money you have, the greater your merit, as if morals, ethics, intellect and integrity are commensurate with wealth. Time and again, this aphorism has been proven utterly bereft of sense, honesty or integrity, yet it persists and in today’s climate (especially in politics), is getting worse. This cult-like worship of wealth relies like all religions on dogma and faith instead of knowledge and understanding, which is also endemic to broad swathes of American culture (though not necessarily to many Americans themselves). It is also especially prevalent in the art world, where if enough (usually very wealthy) people tell the same lie, it becomes an accepted truth. On numerous occasions there are works that might in reality be bereft of artistic, cultural or ethical integrity, but they are still considered of extremely high merit because of an artificially high price-tag or a perceived rarity (even when some can be proven were cranked out in little time alongside two hundred exactly like it at a cost similar to a moderately acceptable restaurant meal).

Looking out upon that landscape, as an artist with dreams of making a living from their art (even if immediate goals are ever so humble), the challenges are seemingly insurmountable. For any creative unknown to the market, demands placed upon them by those who appear to hold the key to any progress, such as art fairs, agents and galleries (not all, but many), can be so arduous, so obfuscatory, so utterly exhausting, that it is all too easy to consider that any success requires actually very little art and mostly the ability to hustle effectively. For an artist this can be a special challenge, because they’re … well … an artist, and not actually … you know … a hustler.

In the literary world there are agents who will take a written work and represent it to the publishing industry in a way that the author gets paid something and is able to benefit from their work. In subsequent years, when their work is re-printed or optioned for use by – say – the theatre, the author earns royalties. It’s a system that works and for a good author, they can earn a decent living from it. When galleries, art fairs and the like automatically have their hand out to an artist they are ostensibly representing (and not for insubstantial amounts, either) then only the already monied are able to progress. If I paint a painting of something, I’m then made to pay money to have it exhibited for the financial benefit of the exhibitor, with a few crumbs paid my way if it actually sells. If I’m lucky enough to have sold the painting and it re-sells later, I see nothing from that re-sale. There are no royalties for artists (except for commercial exploitation, such as prints). The cost of exhibiting is such that the price tag of the painting must be considerably higher than frequently initially regarded (or subsequently maybe considered prudent) to cover costs, fees and the gallery’s substantial percentage so I might see something at the end of the day, certainly a poor gesture to represent my years of experience, cost of materials and the heart and soul that was poured into the picture itself. I already paint a good painting, but that’s no guarantee a potential buyer is going to agree with such a price tag. If I wasn’t an autotelic artist, why bother painting anything?

In 2008, Damien Hirst made waves in the art industry when he self-represented at a Sotheby’s auction. £111million was eagerly forked out by buyers hungry to invest in the superstar’s name. He has a factory where works bearing his brand are cranked out to supply market demand. This is what successful art has become – a cheaply made but expensively sold mass-produced commodity to stand alongside Nike, Apple and Mercedes-Benz, the homogenisation of creativity, the mediocritisation of the exceptional. Hughes declared Andy Warhol to be one of the most stupid people he had ever met because Warhol had nothing to say. Maybe Warhol did have something to say after all, even if his message of mass consumption and the devaluation of the message of art had yet to reach the level it has now, a level even Warhol could not have foreseen when he was at his most incisive.

Much has happened in the art world since 2008, and from this perspective, with little improvement for the artist. Artists rights for re-sale royalties still do not exist. Exploitation remains rampant, and despite the bursting of the contemporary art bubble in the late 2000s, dealers and investors continue to cultivate prices to improve the value of their stock without benefits to artists. Hirsts are not selling for anywhere near what they once were, likely due to an over-abundance of his brand alongside an increasing underlying cynicism regarding the artistic merit of his work (and some methods allegedly used to artificially inflate prices of certain items). There are pieces by others that are selling for decent sums, and in due course new generations will emerge with their own offerings to the world that will be considered worthy of investment and celebration. These however remain a tiniest fraction of a percentage of the art world at large, and I’m referring to works that are actually good quality, have high artistic merit which includes – above all – being beautiful. I see amazing works by relatively unknown artists languishing in anonymity, undervalued and unloved because it is either inconvenient to an existing market still obsessed with monopoly, or there is no hustler to champion that artist and/or their work.

Even in this age of access-all-areas-internet, which has seen a flourishing of virtual galleries and would-be dealers and agents online, there are so few decent works championed by investors or even art lovers. One could imagine that in the fullness of time the dominance of agents, dealers and the contrivances of the market would diminish in the light of greater direct accessibility to artists and their work, but there will always be those who will seek to manipulate the market however they can to benefit themselves, and that includes denigrating and diminishing that which they have no control over, such as online access. Hirst set the precedent with his Sotheby’s auction in 2008. Artists selling directly may have a greater chance of making their way in the art world financially if agents and dealers continue to fail artists, but it is up to artists to find those channels themselves, or agents as there are in the literary world, who take it upon themselves to champion works of merit and actually take care of their artistic protégé.

Can an artist’s work speak for itself? Or must there always be branding required to speak for the value of the art? Are the majority of artists condemned to spending less time on art so they can spend more time hustling? Is it still possible in this world to be a relative unknown and still make enough to earn a living from what they love? Has art moved away forever from meritocracy, doomed forever to the whims of the plutocracy?

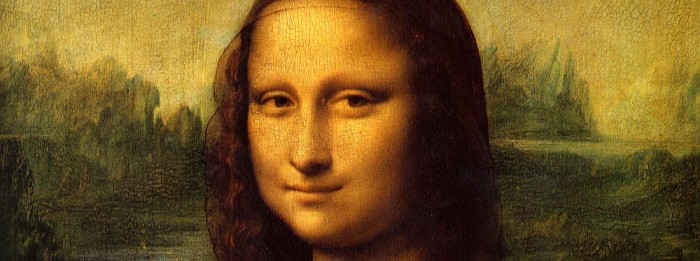

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (a.k.a. La Giaconda, La Joconde), c. 1517. Oil on wood panel, 77cm (30.3in) x 53cm (20.8in), Musee du Louvre, Paris.

Would Leonardo da Vinci have ever been able to recognise the art world as it is today and the way his work is considered and valued by the modern market? I think he would have found it baffling and counter-intuituve, if not utterly incomprehensible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.